Yaniewicz

Celebrating Felix Yaniewicz and the First Edinburgh Music Festival

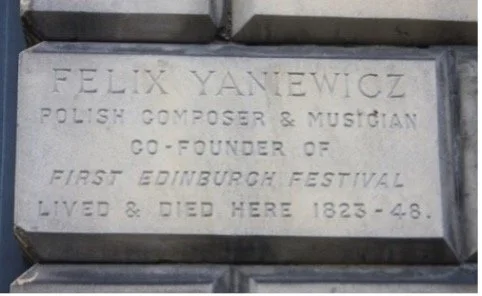

At 84 Great King Street, an inscription on a cornerstone by the door records ‘Felix Yaniewicz, Polish composer & musician, co-founder of First Edinburgh Music Festival, lived and died here 1823-1848’.

84 Great King Street Inscription

Image: Stephen C Dickson

Last month saw the launch of a project to mark his musical legacy in Scotland, which will culminate in 2022 with an exhibition at the Georgian House and concerts by the Scottish Chamber Orchestra.

The project came about with the chance discovery of a beautiful square piano, dated around 1810. Above the keyboard, a gilded cartouche with painted flowers and musical instruments bears the label ‘Yaniewicz and Green’ with addresses in fashionable areas of London and Liverpool.

Inside the piano, the signature in Indian ink has been matched with the marriage certificate of the Polish-Lithuanian composer and violin virtuoso, Felix Yaniewicz (1762-1848). The piano had originally been found in dilapidated condition by early keyboard expert Douglas Hollick, who spent some years restoring it before it was put up for sale two years ago. By chance the advertisement was spotted by one of Yaniewicz’s surviving descendants. ‘It was a thrilling moment’ recalls Josie Dixon. ‘Yaniewicz was my great-great-great-great-grandfather.

When I was growing up, his portrait hung in my grandmother’s cottage: a handsome, enigmatic presence with more than a touch of Mr Darcy.

Discovering this instrument with a very direct connection to my ancestor inspired me to find out more about his story.’

Josie hatched a plan for a crowdfunding campaign, to bring the piano to Edinburgh to mark his musical legacy in Scotland. The project became a collaboration with the Scottish Polish Cultural Association, and funds were raised from all over Britain, Poland, Germany, Norway, France, Italy, Switzerland and the USA. The final donation was made by an Edinburgh doctor in memory of her father, Stanislaw Zawerbny, a Polish veteran, with funds collected at his 100th birthday, and afterwards at his funeral. The Polish Ex-Combatants’ Association offered to house the piano at their former club house on Drummond Place, a stone’s throw from Yaniewicz’s residence on Great King Street.

On 10th November 2021, the piano began its journey north from the restorer’s workshop in Lincolnshire to its new home in Edinburgh. Its arrival was celebrated with two inaugural recitals, by Steven Devine and Pawel Siwczak, setting Yaniewicz’s music in the context of contemporary composers from across Europe, and from his native Poland. Next summer the piano will make a shorter journey to the Georgian House, where it will be on display alongside family heirlooms passed down the generations among Yaniewicz’s descendants. These musical instruments, portraits, personal possessions and letters have a remarkable story to tell about the life of a celebrated musician who changed the course of Scottish musical history.

He was born Feliks Janiewicz in 1762 in Vilnius and rose to prominence as a violinist in the Polish Royal chapel. King Stanislaus August Poniatowski paid for him to travel to Vienna, where he encountered Haydn and Mozart. Mozart’s nineteenth-century biographer Otto Jahn speculates that his lost Andante in A major K470 may have been composed for Yaniewicz. Michael Kelly, a famous tenor, wrote that while in Vienna he was privileged to hear one of the foremost violinists in the world: ‘a very young man, in the service of the King of Poland, he touched the instrument with thrilling effect, and was an excellent leader of an orchestra. His concertos always finished with some pretty Polonaise air; his variations were truly beautiful.’

Yaniewicz travelled to Italy and then to Paris, where he made his concert debut in 1787, and found a patron in the Duke of Orléans. A few years later, with France in revolution and his native land in political meltdown, he fled to Britain as a refugee and joined a community of musical emigrés in London.

There he played in Salomon’s orchestra, conducted by Haydn, performing solo concertos at the Hanover Square Rooms in 1792. In Bath he was hailed as ‘the celebrated Mr Yaniewicz’ - now spelling his name with the anglicised Y which he adopted for the rest of his life. He toured the country as a charismatic performer and energetic impresario; in Dublin his concert series in 1799 was billed as ‘Mr Yaniewicz’s Nights’. He was a founder member of London’s Philharmonic Society and mounted the first British performance of Beethoven’s oratorio, Christ on the Mount of Olives.

In 1799 Yaniewicz moved to Liverpool and married an Englishwoman, Eliza Breeze. A profile in the Monthly Mirror records that ‘he combines the utile with the dolce. He is married at Liverpool; leads the concerts; and is (à la Liverpool) a man of business.’ An enterprise dealing in musical instruments marked a new strand to his portfolio, with a warehouse in Lord Street, in partnership with John Green, the origin of the square piano. Another survival of Yaniewicz’s Liverpool enterprise is a beautiful Apollo lyre guitar, now in the Royal Albert Memorial Museum in Exeter.

Yaniewicz had first given touring concerts in Edinburgh in 1804. His recital at the Theatre Royal – a venue which had taken a central place in Scottish cultural life after Sir Walter Scott became a patron in the 1790s - was hailed as ‘a perfect masterpiece of the art. In fire, spirit, elegance and finish, Mr Yaniewicz’s violin concerto cannot be excelled by any performance in Europe’. So perhaps it was not surprising that it was here that he undertook his boldest initiative, as co- founder of the first music festival in October 1815. Before the year was out, he and Eliza moved to Scotland and made Edinburgh their home for good.

Among the memorabilia on display at next year’s exhibition will be a first edition of An Account of the First Edinburgh Music Festival by one of its secretaries, George Farquhar Graham.

The volume is inscribed on the flyleaf ‘To Mrs Yaniewicz, as a small mark of the author’s esteem and friendship.’ Farquhar Graham’s account gives an evocative insight into the atmosphere and excitement surrounding the festival, in the build-up to the first concert in Parliament Hall:

‘the large and beautiful orchestra filled with eminent performers; the multitude of well-dressed persons occupying the gallery… the novelty of the occasion… together with the expectations of the serious and magnificent entertainment which was about to commence powerfully contributed to produce in every one a state of mental elevation and delight, rarely to be experienced.’

Haydn’s Creation and Handel’s Messiah were performed alongside operatic arias, Haydn symphonies and Yaniewicz’s violin concertos. Evening concerts in Corri’s Rooms were scarcely less ambitious, featuring symphonies by Mozart and Beethoven. Yaniewicz led the orchestra throughout.

Farquhar Graham presents the Festival as a turning point in Scottish musical taste, moving away from national folk culture and towards the classical, continental tradition that Yaniewicz represented, trailing clouds of musical glory from his encounters with Haydn and Mozart in Vienna. At the end of his preface, Farquhar Graham dared to speculate about the legacy of this foundational event in the nation’s musical culture:

‘it has excited much temporary interest – and it may be followed by important consequences, at a time when the hand that now attempts to describe its immediate effects, and the hearts of all who participated in its pleasures, are mouldered into dust.’

If the founders of the Edinburgh International Festival, in the aftermath of the second world war, can be seen as the successors of their counterparts in 1815, Farquhar Graham’s prediction has been more richly fulfilled than he could ever have imagined.

Yaniewicz is buried in Warriston Cemetery, where his gravestone commemorates ‘a most eminent and accomplished musician…honoured, loved and regretted.’ Here on the weekend of the concerts at Drummond Place, the Polish Consulate laid a wreath in national red and white, and underneath it the Friends of Warriston have planted rue, the national flower of his Lithuanian birthplace.