A Singer’s Life Pt34

As Lockdown relaxes, I feel it might be sensible to bring this series of articles to a conclusion soon. I will write the occasional article for the Edinburgh Music Review and hope soon to be able to review live music again. My plan is to turn these musings into an actual book, and I hope you the readers will support this project. Having just produced my first solo CD, I might as well go the whole hog and write a book!

This week I thought I might write a bit about teaching singing, which is what a large number of older singers have done over the years. I have been enormously lucky over the past 40 years or so to be in almost continual employment as a professional performer, both in Britain and abroad, and it was only after my disastrous fall in Vietnam in 2018, resulting in a broken vertebra, hospitalisation and months of recovery that I have had to rein in my performing career. I had to cancel four operatic contracts in 2018 and 2019, which was a huge blow both financially and professionally, and the prospect of much more opera for me is limited. The coronavirus pandemic has also been terrible not just for me but for all my colleagues.

I still have a few potential contracts in the pipeline, because, as I have written in A Singer’s Life, roles for a bass are often slow moving or sedentary. I am now looking at roles for old, possibly blind, partially immobile men (they often seem to be blind, but that’s not yet one of my problems!). Fortunately, the world of opera can oblige, and I am hopeful of a certain amount of future work!

However, it must be said that the most likely continuation of my career will revolve around concerts with choir and orchestra, like Bach Passions and Requiems, and solo recitals with just me and an accompanist. My recent venture into CD production seems to have been successful so far, and I plan, with Jan Waterfield, to do a sort of album promotion tour when allowed by the government.

I am already working on a second CD to be released next year, with more singers, since a diet of bass singing, although marvellous of course, can be a little monotonous on the ear. I am planning more songs by the Scottish composers Ronald Stevenson and Francis George Scott, but also vocal quartet music by Stevenson, previously unrecorded. I have signed up four of Scotland’s finest singers to join me in the enterprise. I am sure it will be reviewed on the Edinburgh Music Review!

The art of singing teaching is not easy, as previous articles in these memoirs have suggested. Simply because one has been a successful and famous singer does not in any way mean that you will be a good teacher. I have written, for example, that Sir Peter Pears, although one of the greatest singers of the 20th Century, was not a particularly gifted teacher, largely because his own style was so individual that it was impossible for him to put himself in the position of his pupils. Similarly, my favourite singer of all time, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, whom I wrote about in an earlier article, and desperately wanted to have a lesson with, was famously a terrible teacher, as he wanted all his pupils to sound like a lesser version of himself. Norman Bailey, who I worked with in the early 90s, was a wonderful man and a great singer, but his vocal technique was completely different from my own, and his teaching was never likely to help me much.

On the other hand, Hans Hotter, who I have also written about at length in these memoirs, was a splendid teacher, as he never tried to make his pupils clones of himself (as if that were possible!). My first serious adult teacher, Laura Sarti, was a great mentor to me at the Guildhall School and was responsible for my early successes in the profession. She worked out very early that I was trying to imitate my hero, Fischer-Dieskau, but with a voice quite different from his. Consequently, I had a light baritone sound, but also a rich bass voice. Laura managed to put the two parts of my voice together into one homogenous sound, and I became a bass-baritone with a rich basic tone but a light and airy top. This saw me through the first years of my career, but soon created problems as my voice matured. By the time I had reached the age of 30, I had to start making serious decisions.

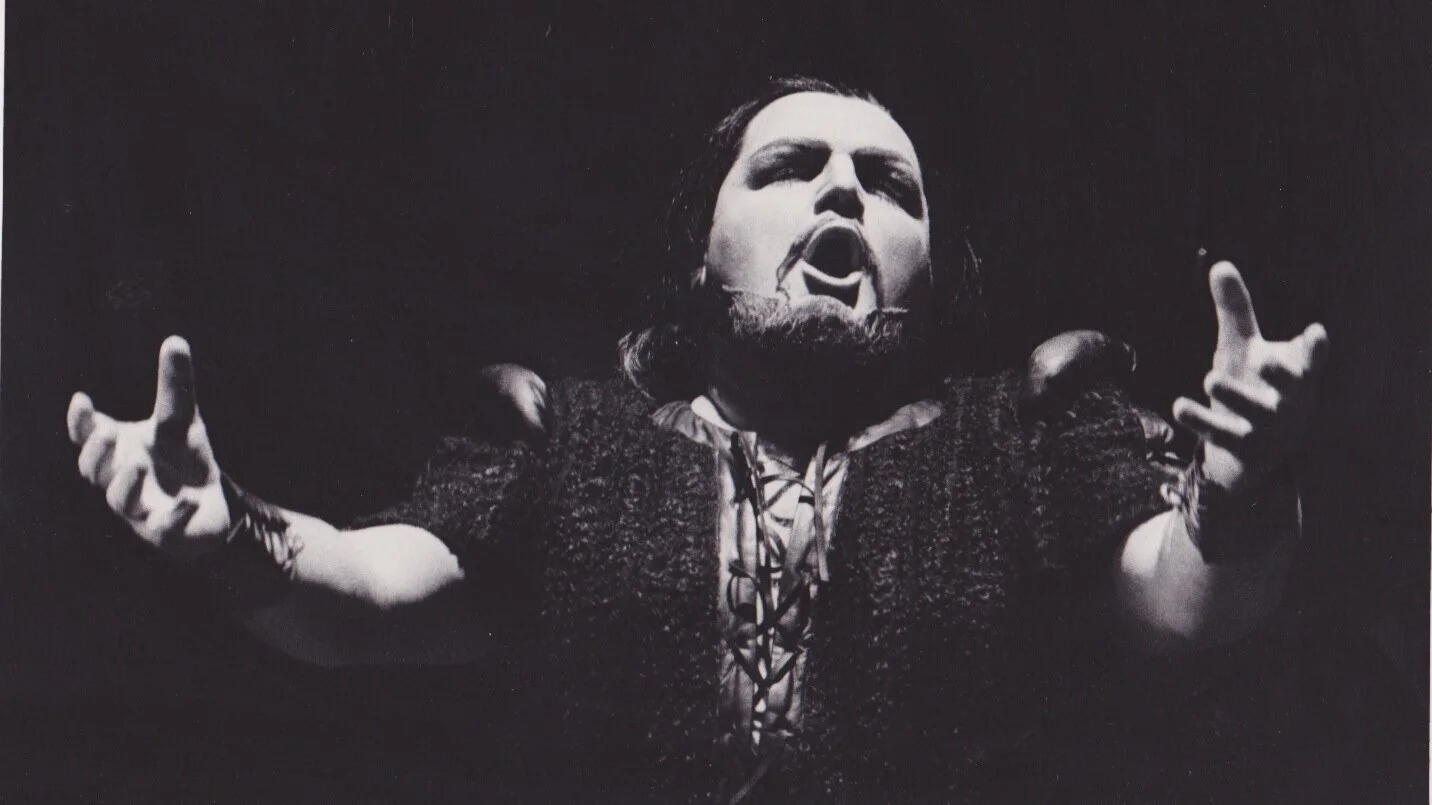

My arrival at ENO in 1987 as Monterone in “Rigoletto” was the beginning of a crunch period for me. Firstly, the challenge of singing in the enormous London Coliseum in the West End from the age of 32 forced me to consider whether my technique was robust enough to cope with the demands of projecting into a wide 2,400 capacity auditorium, without, of course, the benefit of a microphone! The management of the ENO were of a similar mind and recommended that I study with Norman Bailey, the great bass-baritone, famous for his Wotan and Hans Sachs. Consequently, I made several trips to his home in South Croydon for some useful lessons. I had met Norman at Scottish Opera where he had sung Hans Sachs (in Wagner’s ‘Mastersingers’), and knew him to be an extremely lovely man, with a wonderful voice. Our lessons were very interesting, and, in terms of interpretation and breathing technique, helpful, but our styles of singing and voice production were so different that I didn’t feel that I was progressing. I had always possessed a fast vibrato, and I knew it divided opinion. Many reviewers and friends loved its individual sound and slightly old-fashioned feel, but others found it intrusive and annoying. Most critics liked it (“the electric, shimmering voice of BBS” was my favourite from one of the broadsheets!) but others took great exception (“the bleating sound of BBS”). As the 90s progressed, and I sang a huge variety of styles, especially baroque music with its fast runs which I could do easily (my recording on DG of ‘Why do the Nations’ from Handel’s ‘Messiah’ is the fastest on record!), I was able to stay permanently in work but could not quite flip over into star quality and big roles.

I sang in a BBC Prom at the Albert Hall of Ethel Smythe’s opera ‘The Wreckers’ and one of my colleagues was an old friend, the Australian tenor Anthony Roden. He mentioned to me at a rehearsal that he thought I had a nice voice but could sing “a bloody sight better with the right teacher”. After recovering from what I imagined was a terrible slight, I pondered on his words and asked him for a lesson, “if he was so smart!”.

Anthony Roden

I’ll never forget that first lesson in Ealing. He told me firstly that my tongue was getting in the way of the sound, thus creating the fast vibrato. Simply by anchoring the tip of my tongue to the back of my lower teeth (obviously not when using it for articulation!), the air would no longer find a barrier in the middle of my mouth, and could flow out in a smooth and lovely sound. Gosh! That was simple!

Then he told me that my other problem was that I was not thinking like a tenor. I pointed out in a smug way that I was not a tenor and that was probably the reason. Patiently, Tony explained what he meant. A tenor lives to sing high notes. That is his raison d’etre - think Pavarotti, think Mario Lanza, think Andrea Bo...well maybe not. A bass, however, majors on richness of voice, low notes and a smooth, velvety texture. However, this means that he almost inevitably is scared of high notes, and consequently, finds problems at the top of his voice. What Tony was looking for was a quality of thought that, while recognising that, obviously, I was not a tenor, I could imagine taking pleasure in singing bass high notes as much as a tenor would. This was a revelation, and has been proved by the fact that, since I started working with Tony, I have sung Wotan (albeit a shortened version), Falstaff, Britten’s War Requiem and Mendelssohn’s Elijah, pieces that I could not have contemplated singing before, as they were supposedly out of my range.

Finally, I had found out where my voice was really situated. For years, people had been confused by my ability to sing sweetly and quietly at the top, while clearly singing bass parts. I remember way back in 1982, in my first role for Scottish Opera at the Edinburgh Festival, singing the Sergeant of Archers in Puccini’s ‘Manon Lescaut’ and the young, quite famous baritone singing Lescaut coming up to me in a rehearsal and telling me that I was just a lazy baritone. He heard a baritone top from a bass voice. It didn’t help early on that my low notes were rather reluctant to sound on occasions - “he’s not really a bass, you know”, I heard sometimes.

At last, with Tony Roden’s help, I had found my niche, and better later than never! What was also fascinating was that, as my top opened up, the low notes became much firmer. There now was no question that I was a proper bass, and I have remained so ever since. Even the extremely low notes needed for Baron Ochs in ‘Der Rosenkavalier’ are now always there, and audible at some distance!

Next time, I shall write about teaching from the teacher’s point of view, and about my hopes and fears for the future of opera.