The Corries: The early years

It was sometime in the middle fifties as I recall, walking home late through the streets of Edinburgh on a cold November night that I fell in love with the idea of performing and making music. In those dim and distant student days I was the proud owner of a Martin Colletti cello guitar that cut through the brass front line and carried to the far corners of the hall wherever we played. True, it had seen better days but each scrape and scratch on its distressed body reeked of a past history of smoke filled dens where jazz was played and the blues were sung, often in tune, but always discreetly and with a reverence that paid due respect to the unpaid writers and performers who were long gone. Buddy Bolden and Kid Ory’s Creole Jazz Band were the stuff of legend, their scratchy legacy recordings worshipped and studied in a bid to recreate a sound that had its roots in far off places, miles removed from the basement haunts of Edinburgh’s jazz clubs.

Throughout the fifties, In dance halls and night clubs across Scotland, jazz and popular music thrived, until, with the advent of the International Festival in 1947 and the subsequent rise of the fringe, entertainment took on a new meaning as musicians, actors, orchestras and extras flooded into the capital.

The fringe shows captured the attention of the general public providing an alternative to the predictable menu of broadcasting promoted by the BBC. Whilst the Goon Show continued to cheer us into the sixties there was a sense of general disappointment with the quality of broadcasting being offered by the British Broadcasting Corporation. The programming budget for Scotland was paltry and limited to shows such as “The White Heather Club”, broadcast from Glasgow and little else. In an effort to expand and relax the grip of London, the BBC promoted in 1962 the drama “Z Cars”, based in the north of England to appease the growing need for fairer representation of the public’s needs and preferences for more acceptable forms of entertainment.

It was about that time in Edinburgh that a sound producer at BBC headquarters in Queens Street came up with the idea of promoting a programme, to be based on Scottish folk music, to the hierarchy in London. This was to be a new venture conceived and orchestrated from Scotland without oversight from London. The intention to broadcast live to a network audience was adventurous given that there was no network TV connection linking the transmitter in the south to the venue in Edinburgh. The proposal would involve outside broadcasting facilities with all supporting functions.

W. Gordon-Smith was subsequently given permission to float a pilot programme, to be produced, directed and broadcast from Edinburgh, and in a remarkably short time a venue was found and the search for suitable performing talent was undertaken.

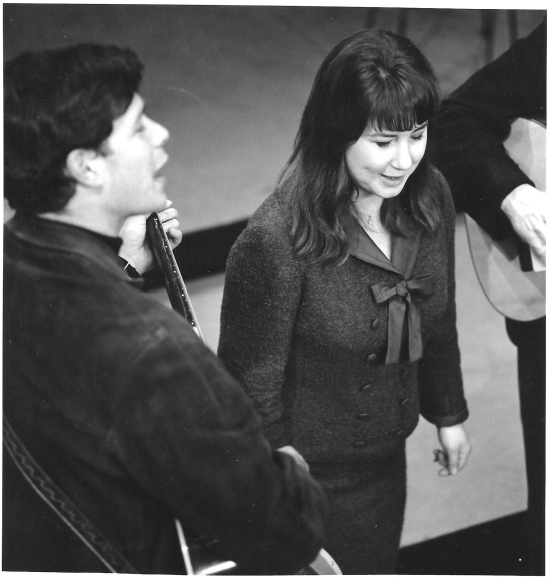

As the founding member of The Corrie Folk Trio & Paddie Bell I had successfully undertaken the promotion of our own festival fringe show, appeared in folk clubs and theatres, been courted by agents and managers all anxious to advance our careers in show business. Since we were all married with families to support, it had never been our intention to give up our day jobs to face an uncertain future in an unstable market. However, all of that was about to change.

We were becoming aware of the rise of interest in folk music which was now thriving in America and in the many folk clubs appearing across Scotland, despite the coverage and investment being pumped into pop music; the rise of Beatle mania and the restless surge being felt by young people anxious for change.

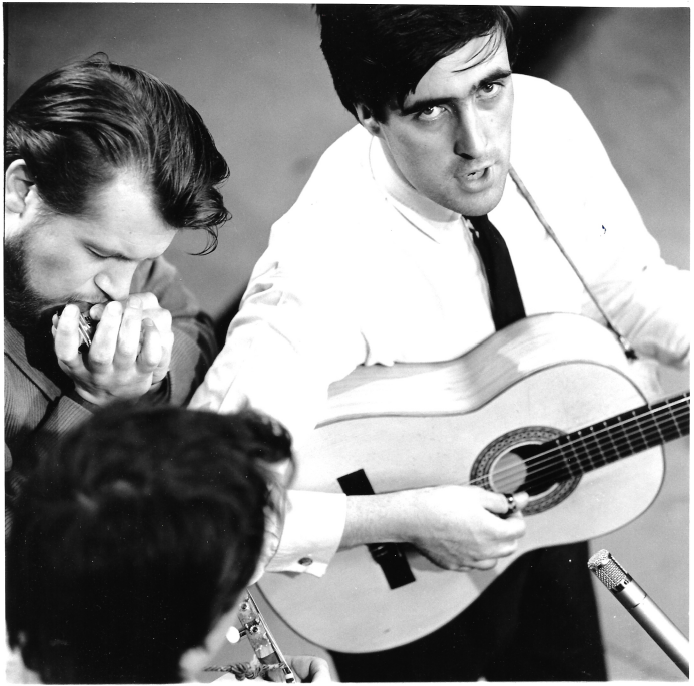

One fine summer’s day in 1963 I was summoned to BBC offices in Edinburgh to discuss the possibility of the Corries taking on the role of the anchor group for a television series of seven shows to be aired in the autumn of that year. A quick decision was required.

After some discussion we agreed, as a group, that we should accept what appeared to be an incredibly handsome offer to an act that had no previous experience of television and which was very much a newcomer to the world of show business. A quick stocktake of our limited repertoire of polished arrangements came as a shock since each show would demand the selection of three or four songs as the director required with no possibility of repetition. Some serious hard work lay ahead.

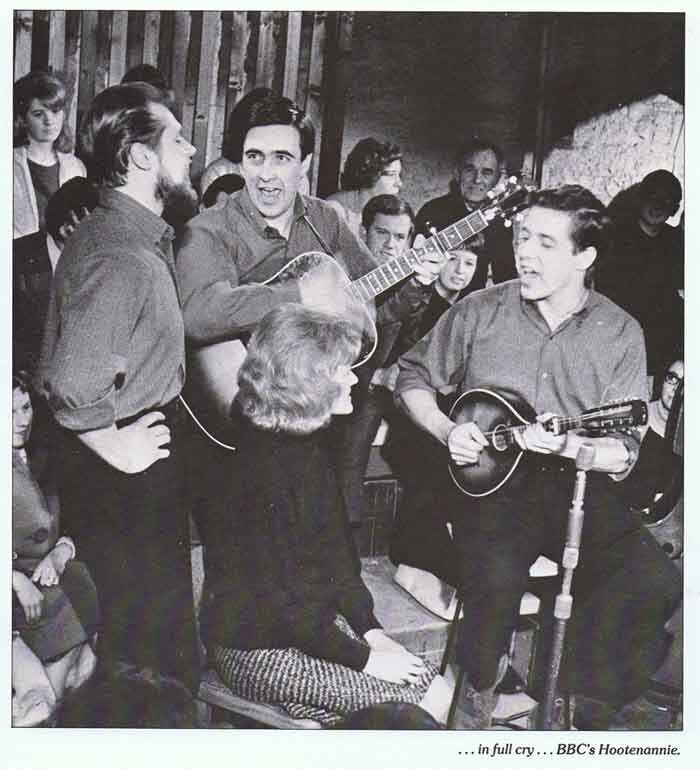

And so it came to pass that the pilot show was launched; to be named The Hootenanny Show; the name derived from a similar current American production and intended to convey all the attributes of ceilidh, singalong and musical soiree. With the appointment of a slightly nervous director from London and no less a figure than Hugh Carlton-Green in attendance the pilot show played out in the cellars under Victoria Street to a younger than springtime audience who joined in the singing and applauded spontaneously as the various acts linked seamlessly with each other without the need for a front of house presenter. This lent the show a semblance of naivety with audience and performers seemingly unaware of the network audience looking in.

In time, word arrived that the pilot show had found favour with those on high and a series of seven shows was approved. The Corrie Folk Trio & Paddie Bell were duly contracted to perform. What we were not prepared for was the almost instantaneous popularity accorded to the show with the result that the run was extended to thirteen, then twenty one and ultimately thirty two shows.

At an early point in the planning of the shows the BBC endeavoured to introduce professional singing groups to lighten the growing nationalistic direction of the shows, all to no avail. After one particular episode we were officially criticised by BBC Northern Ireland as “subversives” much to the delight of the production staff. At no time were we guided in our selection of material or asked to moderate our repertoire. Instead, the continuing flow of fan mail reaching the BBC indicated that the public were delighted with the content, a fact that encouraged us as a group to continue.

Two of these letters were particularly revealing. The first from a lady in the Midlands thanked us for “her weekly serving of musical sanity” while the second, from a bed ridden viewer on the west coast, thanked us for “putting the words back into the music”.

We had no quarrel with either viewpoint.