Meeting Rudolf Nureyev - Pt1

His Leap to Freedom

He was perhaps the greatest male dancer of the 20th century, certainly the most famous. His leap to freedom, an event at the heart of world politics, captured the headlines. I had a ringside seat.

Paris, Théâtre des Champs-Elysées, the Cuevas season, 1961. Dancing the Cat in ‘Sleeping Beauty’, I enjoy my first professional triumph, thanks again to Tchaikovsky*. It’s the talk of the town, more precisely of the balletomanes. A leading light among them was Clara Saint. Daughter of a rich Argentinian family, she had bought an enormous apartment in rue de Rivoli, facing the Jardin des Tuileries and the Louvre. She lived on her own with only her maid for company. We became friends and she invited me to come and stay in her flat till the company went on tour.

I got to know several of her friends, including Olivier Merlin, the ballet critic. All were fanatical balletomanes, attending every ballet premiere in Paris. I was already a soloist with the Grand Ballet du Marquis de Cuevas, on the way to becoming a principal dancer.

One evening Clara invited me to the Paris Opera, to see the Kirov company, visiting from Leningrad. Before the performance Clara’s friend, Olivier, was telling us: “I’ve heard there’s a sensational new dancer called Rudolf Nureyev. Already the Russians think he’s heading for a great career, and only 22 years old. We'll see him tonight!”

Rudolf appeared in baggy folklore breeches and a fluffy shirt. And whatever he did we loved it! He made the rest of the dancers - a huge number - seem to disappear. His grands jetés en tournant around the stage brought the house down. But when he danced ‘Le Corsaire’, the public went wild. Olivier took us into the dressing room to congratulate him and introduced Clara to him. The moment they met there was something between them; what the French call un coup de foudre (a bolt of lightning). Olivier and I sensed it and took a few steps away while they talked and talked and talked.

And that was the beginning of their love affair.

As the three of us left, Olivier said: "Wouldn't it be fantastic to keep this marvellous dancer here in the West?" But then he added: "The Communists are very strict with all their dancers; they can’t give interviews or accept invitations individually. They’re only allowed to go around in the group. If they disobey orders they get sent straight back to Russia, maybe even Siberia. Still, does no harm to dream of him choosing to stay here in Paris."

In spite of the restrictions, Clara - madly in love - managed to meet him after his performances, taking him out to see Paris by night. Apparently, to meet her he used to jump down from his hotel room like a cat in the night. This went on during the Kirov's entire Paris season. That was when I met him. He was still with the Russian group. We took him out on 14th of July, France's National Holiday. He was happy for a few moments, but restless, aware he was breaking the discipline imposed by the Communist authorities. Another evening we went to a restaurant in Les Halles (the old Parisian food market). There we met other dancers from the Paris Opera who immediately recognised Rudolf and were full of admiration. But that night he was in tears; the Soviet minders had discovered that he was going out with Clara in the middle of the night. In fact, they’d given him strict orders to stop those exits immediately, but he had not. That had serious consequences for him.

Then I didn’t see him again for a while but heard daily reports first-hand from Clara. She it was who enabled him to escape from his minders at the airport.

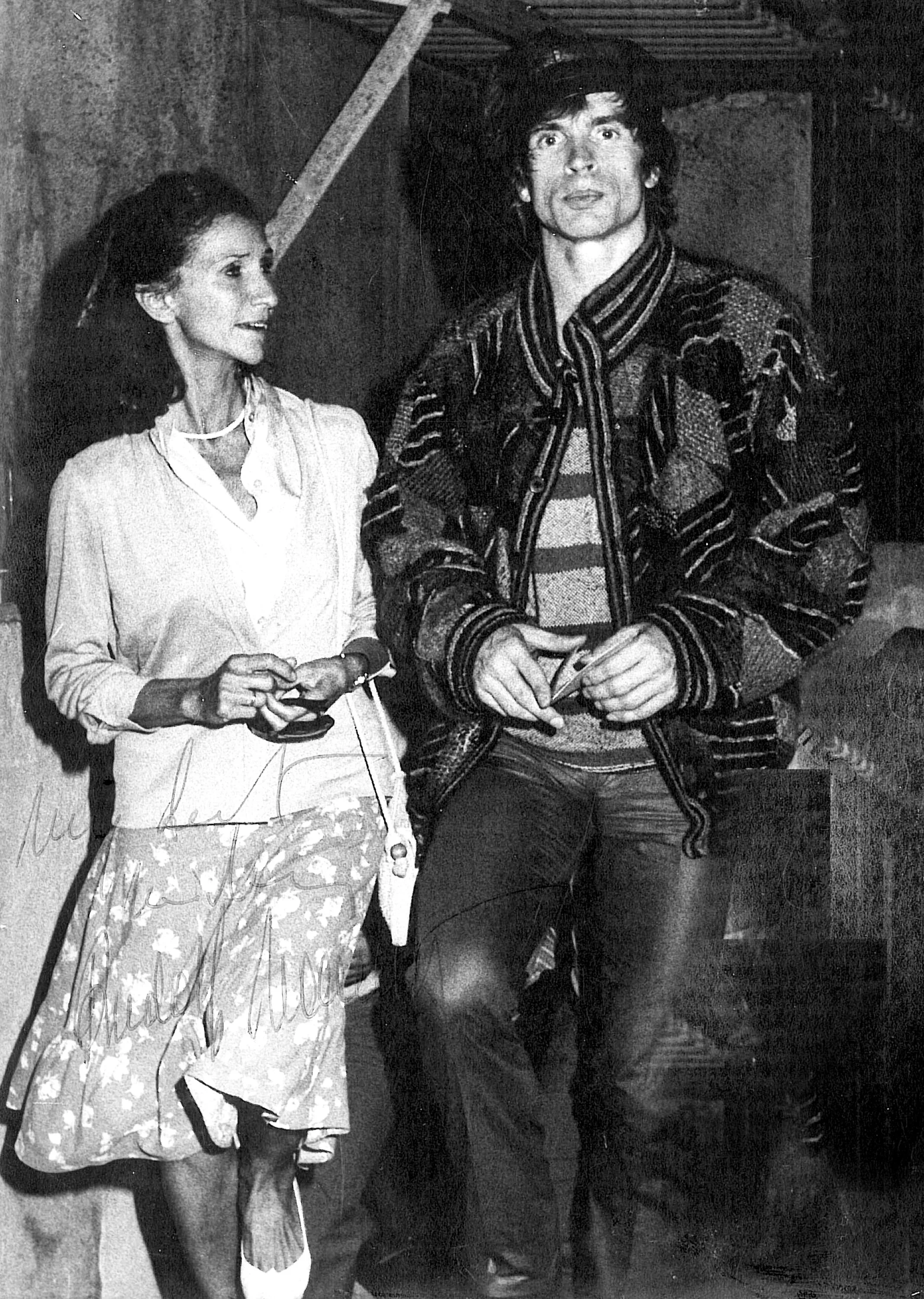

Kalliopi & Rudolph - Photo: Georgos Turkovasilis

Decision at the Airport

At Le Bourget airport the Russian troupe are just about to fly to London to perform there for several weeks. Each dancer is given a ticket and in they go to the plane. When Rudolf puts out his hand for his ticket, two heavies grab him and say: "You're not going to London! Back to Russia. No ticket for you!”

While this is going on, Olivier has come along to say good-bye. He takes in the whole scene: Rudolf being held back, while the rest are disappearing into the plane. Suddenly there is only Nureyev, the two heavies and Olivier in the waiting room. Immediately Olivier goes discretely to phone Clara, tells her to come straight to the airport. It's five in the morning. Clara arrives in slippers and nightgown, just a coat over her shoulders. Olivier takes her aside and they both go to the airport police office asking what can be done for Rudi: is there any way he can stay in the West?

The officer tells Clara: “We can’t intervene, but if you are brave enough, go and whisper in his ear to come running into our office. This is French territory, and we are the police. So we'll close the door with him inside and forbid the minders to come in. He then asks for help from the French authorities; we request a white passport for him and he’s free.”

That is what Clara does. She walks slowly towards him, the heavies giving her black looks: “I want to say goodbye to Rudolf.”

They know Clara is the reason he’s going to be punished by the Soviet authorities, but they let her approach him; she embraces him in a long hug, whispering into his ear:

“Go! Go! To that door!” - she indicates it with her eyes - “The French police are waiting for you for there. Freedom! Quick, go!”

She then walks slowly towards Olivier, almost in tears, but confident that Rudi will be as brave as her. She gets near Olivier; they give the impression they are leaving, wave good-bye to Rudolf. Keeping his wits about him, Rudolf waits a few moments, so the minders won't suspect anything; in a split second he does what Clara told him. He digs his elbows into both minders and dashes into the police office. The agent on duty informs him very coolly: "It is official policy in cases like yours to leave you for half an hour in a closed room to think, entirely on your own, and decide if you really want to defect and stay in the West".

A short time for a big decision. Rudolf duly walks out of the room with a smile on his face to say: "Yes, I want to stay!"

After that Clara arranged for Rudi to shift from house to house all over Paris, until his white passport came through. That took several weeks in which everyone had to keep quiet about his whereabouts. The paparazzi came snooping round at the Théâtre Champs-Elysées every day: “Where’s Rudi?”

Nobody had a clue, not even me, living with Clara at that time. The only thing I knew was what Clara told me about the airport events; and that’s why I can write about it now so explicitly. Several times the paparazzi followed me:

“Hey! Where is he? Where’s Rudi?”

"I don't know. Please leave me alone, I just don't know!"

I started getting scared and moved out of Clara’s place back to my hotel.

By that time Rudi’s white passport was ready. He was an international free man, ready to become the international big star.

If you’d like to know more, a recent film The White Crow, directed by Ralph Fiennes, gives an engaging account, climaxing with his leap to the West. It’s pretty close to the facts, with some fine dancing by the star, Oleg Ivenko.

Kalliopi in 1961 - Photo: Elisabeth Spiedel

* See Musical Muscles, Part 2, where I describe how Tchaikovsky has inspired my dancing.