Cathedrals: The West

Having started with Lincoln, my tour of the great British cathedrals has taken us up the east coast to Scotland, with its very different choral tradition.

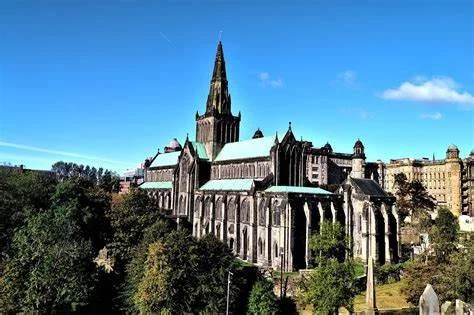

Glasgow Cathedral

I didn’t say much about Glasgow Cathedral, that splendid building in Glasgow’s east end between the Necropolis and the old Infirmary. The cathedral, dedicated to St Mungo, was consecrated in 1136, and is the oldest cathedral in mainland Scotland and the oldest building in Glasgow. Until I sang a Mozart Requiem there in September 2019, I had always assumed that, like St Mary’s in Edinburgh, it was a fine Victorian church, built in the Gothic style. I must admit to complete ignorance of its true history as one of the most important mediaeval buildings in Scotland. Along with St Magnus’ Cathedral in Kirkwall in Orkney, it is the only mediaeval cathedral to have survived, mostly intact, the Reformation in Scotland. The ruins scattered around Scotland are a sad testimony to that destructive era!

St Mungo’s was founded in the 12th century, the present building replacing the original 1136 structure. It was dedicated in 1197, but most of what we see now represents the reconstruction of the 13th century. After the Reformation, the church was split into three parts, but the Victorians seem to have realised the damage done, and they largely restored the cathedral to its former glory.

Glasgow Cathedral

It’s a quirky building, built on various levels, with a very decent acoustic, and is well worth a visit. It is presently administered by Historic Scotland and is something of a surprise within the Victorian grandeur of Glasgow. The nearby Necropolis, an extensive Victorian cemetery built on a hill overlooking the cathedral, is also well worth a visit.

Leaving Glasgow, one should point out the several ruined abbeys of the Scottish borders, another grim reminder of the destructive power of the Reformation. I, as an atheist, make no comment here about the necessity for change that brought about the Reformation, sweeping away centuries of corruption in the mediaeval Catholic Church. I lament only the fact that so many things of beauty - buildings, sculptures, beautiful windows- were all destroyed in the name of God. The border abbeys, Melrose, Dryburgh, Jedburgh and Kelso are still well worth visiting, despite their ruinous state. Indeed, many visitors, in both directions, north and south, completely miss the wonders of the Borders as they rush to or from Edinburgh and Glasgow. Don’t make that mistake!

Carlisle to Liverpool

I almost made a mistake myself here, as I was about to skip south to Lancashire without mentioning the exquisite jewel that is Carlisle Cathedral. My excuse is that I have never been there and didn’t know of its existence. Obviously, I have never sung there, but it looks jolly nice. Having started as an Augustinian priory, it was made a cathedral in 1133, and over the years, both a Dominican and a Franciscan Friary were established close by. After Henry VIII’s Dissolution of the Monasteries from 1536, the friaries were dissolved, and the cathedral was run as a secular chapter, like Lincoln. The most important feature of Carlisle Cathedral is its magnificent East Window, with superb tracery dating from about 1350 in “Flowing Decorated Gothic Style”. Let’s all visit!

Continuing down the west of England it is clear that there is a slightly strange anomaly. After Carlisle, there is a remarkable lack of cathedrals for many miles. Nothing in Lancaster (well, there is a 19th century church upgraded to a cathedral in the Catholic rite, but…..), nor Preston, and while Manchester has one, it was only upgraded from a Collegiate church (very fine, nonetheless) to a cathedral in 1847. Liverpool, of course, has two, but neither are old. The Anglican one was built between 1904 and 1978, and is the largest cathedral in Britain, and the eighth largest church in the world! The Catholic one, Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral, was opened in 1967. I’m afraid I haven’t sung in either!

Chester Cathedral

Finally, at the border of Cheshire and Wales, we find the ancient city of Chester, founded by the Romans in 79AD. One of the last towns in England to fall to the Normans after William’s conquest in 1066, it became a hugely important strategic town, commanding the Welsh border, and the main roads towards the port of Liverpool. It remains, like York, one of the great walled mediaeval cities of England, and is a delightful place to visit. Like Berwick, in a similar position at the Scottish/English border, also a walled town, one of the first things you notice are the accents. Without any outward sign, a person you may meet in the street sounds either Welsh or Scouse (in Berwick, it’s Scots or Northumbrian), a typical feature of border towns the world over.

Chester Cathedral

I have been privileged to sing several times in Chester Cathedral, a splendid building which makes up for the cathedral drought of north west England. In 1093, a Benedictine Abbey was established in Chester, and this abbey church was expanded and altered over the centuries. After the Dissolution of the Monasteries in 1538, the abbey church lost its shrine to St Werburgh (an Anglo-Saxon princess who was made a saint in the 10th century), sadly vandalised by zealots, but was created a cathedral by order of Henry VIII in 1541. The various changes to the church allow us to see, in one building, excellent features of Norman, Gothic and Perpendicular styles, and it has a splendid acoustic. I sang Verdi’s Requiem, Britten’s War Requiem and Mozart’s Requiem and Solemn Vespers, and formed a good friendship with the local Music Society there.

Worcester, Hereford, and Gloucester

Skirting Wales, our journey south takes us to the three great cathedrals of west central England, Worcester, Hereford and Gloucester, these three forming the locations for the famous Three Choirs Festival, held annually at the end of July. Typically, I have sung in all three, but not in the Festival! Most recently, I sang in Hereford, which I had never visited. It is a beautiful building, started in 1079, and expanded mostly in the 12th and 13th centuries. It has an extensive and justly famous library, whose prize possession is the Mappa Mundi, a mediaeval map of the world (hence the name!), created around 1300 by Richard of Holdingham. This is a most extraordinary document, a circular map drawn on vellum, with Jerusalem at the heart of the circle, and is the largest mediaeval map in existence. It is now housed in its own special museum in the cathedral close and is well worth the trip!

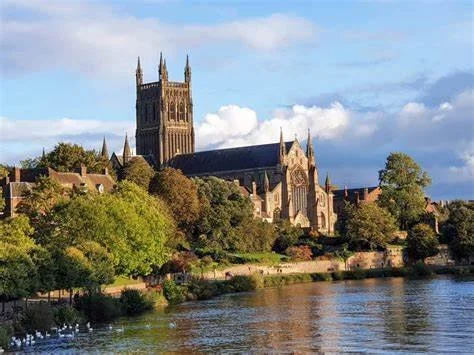

Worcester Cathedral, founded in 1084, benefits from its fantastic situation on the bank of the River Severn, looking across the river to the county cricket ground.

Gloucester Cathedral, founded in 1072, I found slightly surprising, in that its nave is early Norman, in the heavy Romanesque style. One is so used to soaring vaults with high windows that discovering a squat design (like Durham) is somewhat unexpected. It is magnificent, nonetheless, and obviously stunning in its antiquity. The later Gothic choir seems to stand out even more. Harry Potter fans will recognise, in particular, the cloister where our hero spends a lot of his time making mischief! The first, second and sixth Potter films were extensively shot in Gloucester.

I should mention in passing, the lovely abbey church of St Mary in Tewkesbury, between Worcester and Gloucester, not a cathedral, but one of the finest Romanesque Norman buildings in England, begun in 1121. It was also the venue for a famous ‘Messiah’ in which I sang the bass solos, the story of which you will find in various chapters of ‘A Singer’s Life’. Suffice it to say here that there was a certain disagreement between bass soloist and conductor, which resulted in the longest ‘Messiah’ I have ever sung (totally uncut!), but also, apparently, the best I have ever sung!

Llandaff Cathedral

A quick trip over the border into Wales allows me to flag up Llandaff Cathedral in Cardiff. I have never sung there, but it seems to have been a place where persistence ruled all. Founded in the 12th century, it was badly damaged / almost destroyed in 1400 (Owain Glyndŵr’s rebellion),in the English Civil War and in the Great Storm of 1703. Major reconstruction took place in 1734, but wartime bomb damage in 1941 nearly destroyed it again, blowing the roof off the nave, south aisle and chapter house. Rebuilt after the war, lightning severely damaged the organ in 2007, but still it soldiers on. Bravo Welsh people!

Bristol, Bath, and Wells

Moving south again, we come to south-west England, and another anomaly. Bristol is by far the largest city in the region, but the history of its cathedral is curious. The present building started life as an Abbey church and was extended but without a full nave in the 14th century. At the Dissolution, it became a cathedral, but the partly built nave was demolished. In the 19th century, it was decided to build a new nave, and a west front with towers, and that’s what we see now. Interesting but hardly earth-shattering in terms of architecture. The parish church of St Mary Redcliffe (constructed between the 12th and 15th centuries) and one of the most beautiful Gothic buildings in England seems far worthier of cathedral status but lacks it. I sang there once years ago and found it a delight.

Not far from Bristol are the twin glories of Bath and Wells. Bath Abbey is a wonderful church, a splendid example of the Perpendicular Gothic style, with magnificent fan vaulting. In the Middle Ages, it served as a sometime cathedral, but, after much disputation, the seat of the Diocese of Bath and Wells was consolidated at Wells. Bath Abbey became a most grand parish church. Set within the beautiful old city with its Roman baths and superb Georgian architecture, it is well worth a visit, if you can deal with Bath’s interminable traffic problems. I sang in a fabulous Verdi Requiem in Bath Abbey over 25 years ago, a performance etched in my memory because my then baby daughter Katrina began snoring in the Agnus Dei and had to be whisked out by her mother!

Not far to the south west lies the small town of Wells, site of one of the glories of Gothic architecture, Wells Cathedral. I have sung in Wells, but it is so far back in the mists of time, I have no recollection of what I sang! I do remember going to Wells as a child, when my parents took me on holiday to Teignmouth in Devon, a journey of epic quality. My father was the only driver, and there were no motorways, so the drive from Edinburgh took literally days. All the towns now bypassed by motorways had to be driven through, starting at Carlisle and continuing through the Midlands and on down where nowadays the M5 runs. I recall we stayed somewhere near Wells, as I have souvenirs of the Cathedral, along with mementos of Wookey Hole Caves, Glastonbury Hill, Bath and the Cheddar Gorge.

Wells, as I pointed out above, won the right to be considered as the main seat of the Bishop in mediaeval times, and it is a truly superb building. In the 14th century, the vicars’ close and the bishop’s palace were added to the environs of the cathedral, and the whole site is a wonderful mediaeval mini village.

It must be said that the cathedrals of England are some of the finest buildings ever constructed, and, considering the primitive technology available at the time, they must be judged as wonders of the world. No doubt many were the results of vain men wishing to preserve their legacy, but the creation of these splendid buildings throughout the country does offer an insight into the mediaeval mind, the vision to build something, largely dedicated to a supreme being, with no temporal reward and at vast cost. As I have written, I myself do not possess a religious faith, but it is fascinating to see what such a faith can create, adding religious music to the architectural wonders too. I was always saddened when a friend of mine, who was a humanist celebrant, explained that his Humanist services could not in any way include religious music. I believe this is changing, and quite right too. One can love religious music without believing, so why not include some of the most beautiful and moving music ever written!

I have sung in Exeter Cathedral in Devon, built between 1112 and 1400, a splendid fusion of Norman and Gothic architecture. Since there is no central tower, Exeter Cathedral has the longest uninterrupted mediaeval vaulted ceiling in the world, 315 ft long. Not many people know that! The fifty misericords, the carved seats in the choir, are the earliest complete set in the British Isles, one depicting the earliest known carving of an elephant in Britain. Finally, the Minstrels’ Gallery in the nave has splendid carvings of many lost or obsolete instruments.

Before turning back east, I must mention Truro Cathedral in Cornwall, a magnificent Victorian Gothic edifice, where I sang nearly 50 years ago with the St Andrews Renaissance Group. Many of these cathedrals I have been describing have never heard my dulcet tones as a professional soloist but have warmed to the velvet bass notes I supplied to the Renaissance Group!

Next time, we move back east. We might even cross the Channel!