A Singer’s Guide to the Great Composers: Britten Pt2

Britten and Pears were living in California during World War II and happened upon an article in ‘The Listener’ by E M Forster about the 18th century Suffolk poet, George Crabbe. Pears sought a copy of his narrative poem, ‘The Borough’ and both men were particularly taken with the section about Peter Grimes, a fisherman whose callousness and cruelty were responsible for the deaths of some young boy apprentices. Britten was seized by the need to return to England, and they made the dangerous journey across the Atlantic in 1942, with the very real threat of attack by German submarines.

Once back in the UK, still very much at war and in a precarious position, the two conscientious objectors threw themselves into music making, as their contribution to the war effort. Britten engaged Montagu Slater, a communist poet with whom he had worked in the 30s, to write a libretto based on Crabbe’s poem, and this proved both a positive and a negative for the finished work. Slater’s libretto, amended by Britten and Pears before the first night, hugely magnified the scope of the original, replacing an out and out villain with a nuanced and deeply troubled character, as much a product of societal alienation as one who creates it. Britten wrote that the subject was very close to his heart – the struggle of the individual against the masses. “The more vicious the society, the more vicious the individual.” This was a common theme running through all Britten’s operas, and I think it was the element that gave his works their particular power. One rarely comes out of a production of one of his operas without being made to contemplate the elemental struggle of forces beyond individual control. Slater produced a libretto of enormous intensity, and combined with the sweep of Britten’s musical imagination, ‘Peter Grimes’ is recognised as one of the greatest operas ever written. For me though, the very poetic intensity of the words sometimes works against its clarity, and certainly when singing the opera, one is aware that one is singing quite florid poetry, in opposition to the visceral emotion of the music. On the other hand, whenever involved in a production of ‘Peter Grimes’, you are daily provided with a phrase or sentence which can sum up your feelings on almost any subject!

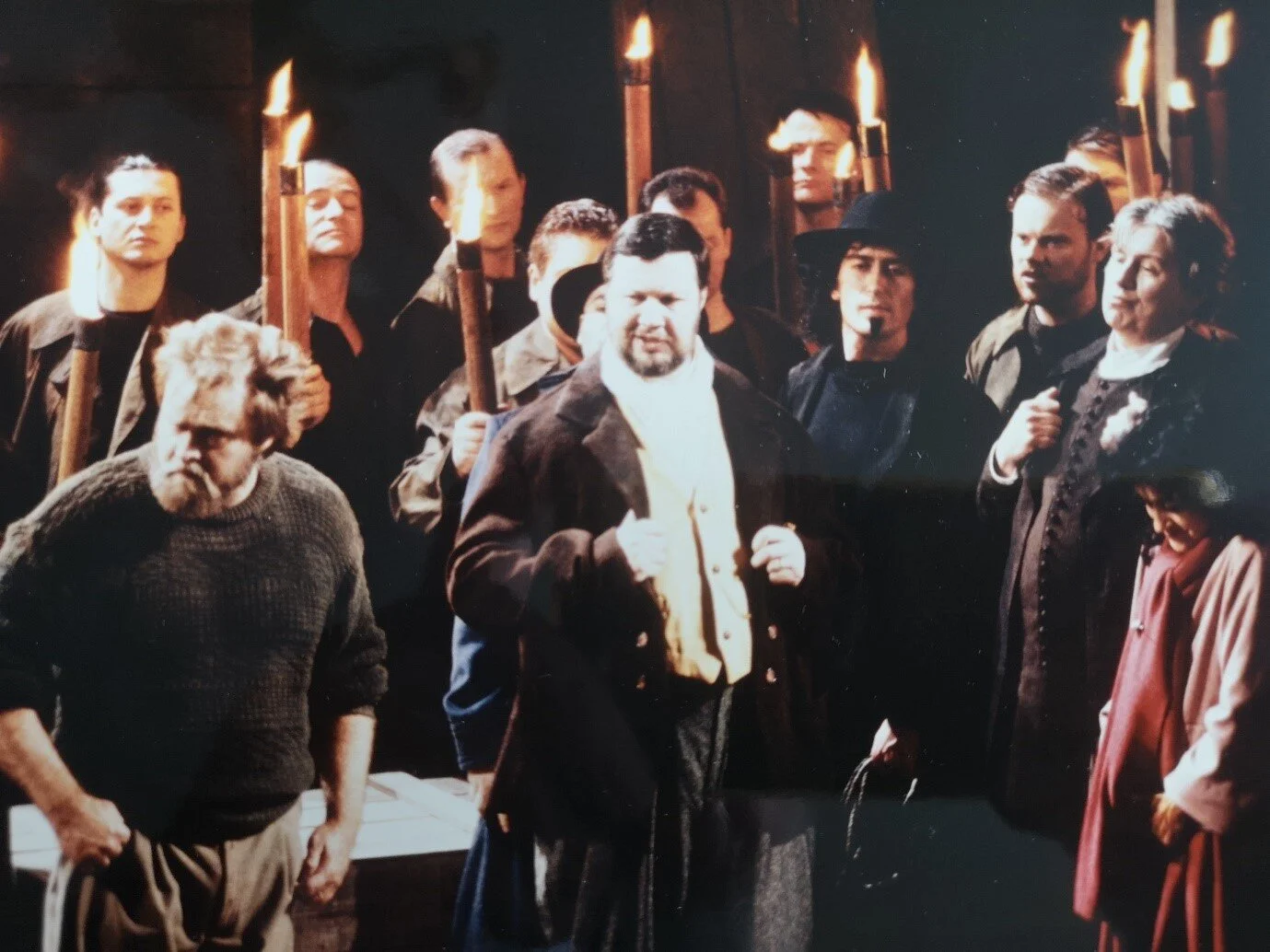

The author, Brian, performs in Peter Grimes in Nantes

I have written fairly extensively elsewhere in the EMR about my take on the opera, and how various productions have added to, and subtracted from, our understanding of the piece. Today, I thought I might explore just how revolutionary this opera was on its premiere at Sadler’s Wells Theatre in London on 7th June 1945, conducted by Reginald Goodall and with Pears as Peter and Joan Cross as Ellen Orford, the widowed schoolteacher who tries to save him from himself. In the course of the preparation for the first performance, Britten and particularly Peter Pears, had been at pains to restrict Slater from any seriously overt sexuality in Grimes’ behaviour, for which we must now be hugely thankful. It is the libretto’s very lack of certainty that makes it so profound, and any production which seeks to emphasise “homosexual oppression” or “unnatural relations with small boys” has missed the mark by a mile! We are touched and moved by Grimes’ tragedy, because we don’t really know what is going on, and indeed the less we know, the more tragic the story.

One of the most interesting features of ‘Peter Grimes’ is that, for a drama which often leaves the viewer exhausted and emotionally drained, there is very little real characterisation. Apart from Grimes himself, who we watch come adrift mentally throughout the piece, there is little development in the personalities of the other roles, and indeed they are to a large extent caricatures. The pompous lawyer, Swallow, who appears the backbone of Borough society, yet lusts after bar girls, Ned Keene the apothecary, who uses his medicines and potions to control people’s behaviour, the Rector, with his pieties and cowardice, Bob Boles, the fisherman who, despite his strict Methodist morality, also lusts after bar girls, the old widow, Mrs Sedley, who thinks she is a detective, Auntie, who runs the bar and supplies drink and “comfort”, Hobson, the dim-witted delivery man with a conscience, all of these are stock characters in any soap opera. Even the two protagonists who are central to the story of Grimes downfall, Ellen Orford, the widow and Balstrode, the retired sea captain, have very little development in their personalities throughout. And yet, at the end when Grimes in his despair and madness sails out to sea and deliberately sinks his boat, we are deeply moved. The endless movement of the sea, and the unchanging lives of the townspeople, despite the great events of the story, remind us that human lives are tiny parts of a greater whole, which follows an inexorable path continuously from day to day.

The role of Grimes himself is a fascinating one, and the extraordinary effect that two great artists have had on the opera over the last 75 years is worth examining. Peter Pears, for whom the role was written and whose voice resonates in every note, was both a magnificent singer, but also a great actor. As I have written, he was a big man, well over six feet tall, and, although quietly spoken, he had a charisma about him which was overwhelming. Even in his sixties, when I first met him, retired from the stage, he could easily dominate a room, and when he demonstrated a phrase or passage in a masterclass or lesson, the sheer intensity of his singing was astounding. I remember him explaining how to sing something, and, unable to show it in words, breaking into song with that great unworldly voice pouring out from his enormous head. It was breath-taking!

He brought to the role of Grimes an intensity and a passion which was completely at odds with his persona as a rather posh English gentleman, and his ability to portray this rough diamond of a fisherman, whose main flaw was his clumsiness and social ineptitude, rather than some evil sexual impulse, made him the ideal interpreter of the role.

However, in the late 60s, a strange fellow from Saskatchewan, who had made his name since the late 50s as a heroic tenor in the German and Italian repertoire, sang Peter Grimes for the first time at the New York Met. This was Jon Vickers, a singer who possessed the most powerful voice I think I have ever heard, and whose interpretation of the role has dominated casting everywhere in the world since that time. He went on to sing it all over the world and record it with Colin Davis in 1978. I saw him sing it around the same time at Covent Garden, and was totally overwhelmed by his performance, both the singing and the acting. He had a wild manic look, and very much stood out from the crowd. His singing, however, was always absolutely controlled, and he had the unique ability to sing wonderfully quietly when necessary. His honeyed mezza voce was spine-chilling and made his madness even more tragic. I never met him, but I was astounded to learn from people who had, that he was rather a short man, well under six feet. He was tremendously muscular, however, and looked much taller on stage (I believe he wore lifts on his shoes), and his personality dominated everyone else. He was famous for giving his all – a colleague of mine reported back from a production of Pagliacci, when Vickers stopped a rehearsal to tell said colleague that, in future, if he didn’t step away from him at the right moment, he would have to kill him, as he was unable to hold back his knife. Scary! Years later, Vickers retired to Bermuda, and when I was there, singing in a production of the Marriage of Figaro, I was furious to discover that the people who were running our show had been invited to dinner with him the night before. Muttering that they couldn’t turn up with all the cast, we’re very sorry etc, cut no ice with me. I’d love to have met him, although he was apparently a very odd chap, with deep Christian fundamentalist beliefs. These beliefs famously prevented him from singing Wagner’s ‘Tannhäuser’, although why this role was so much further beyond the pale than Otello, Canio and Grimes, I’m not sure.

The problem with Vickers singing Grimes, apart from the fact that Britten and Pears hated his interpretation, has been that casting directors frequently look for a dramatic Wagner tenor for the role these days, and apart from Vickers, most of these tenors can’t sing all the intense quiet passages. Stuart Skelton, who I admire enormously and who I worked with in ‘The Ring’ in Seattle, has become the Grimes de nos jours, but when I heard him in a concert version in the Usher Hall a few years ago, he was really struggling in those quiet bits. I will be interested to hear how Allan Clayton gets on in the production, currently (May 2021) rehearsing in Madrid, as his voice is much more like Pears’. He recently sang Britten’s ‘Serenade for Tenor, Horn and Strings’ with the SCO, and I thought he was wonderful.

I have written elsewhere at some length about ‘Billy Budd’, and about my regret never to have been cast in it, but it remains one of the finest operas ever written with its tale of the simple sailor whose life is ruined by the inexorable workings of fate and the disciplinary proceedings of the British navy. The various changes the opera underwent in its composition and performance history are many, and for another day, but all I would say now is that on first hearing it at Covent Garden in the late 70s/early 80s, I have never been moved more by any performance of anything.

The author, Brian, performs in A Midsummer Night’s Dream in Beijing

As well as ‘Peter Grimes’, my career has been strongly affected by ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream’, Britten and Pears’ adaptation of the Shakespeare play, first performed in Aldeburgh in 1960. I have sung Snug the joiner, Duke Theseus and Bottom over a period of nearly 40 years and love this work dearly. From my first rather timid Theseus at Scottish Opera in the early 80s, to recording the role with Sir Colin Davis and performing it at the Barbican in London with the cream of British singing royalty and the LSO, from Snug with Opera North to the same role at the Aix-en-Provence Festival and Beijing, and finally to Bottom with Pacific Opera Victoria in British Columbia, I can safely say that there is not much about this opera that I don’t know. The music is more difficult to learn than Britten’s earlier operas, and, indeed, Bottom is really hard, so much so that I often wonder if Britten secretly had it in for Owen Brannigan who first sang it. The orchestration is magnificent, right from the beginning, with its mysterious rustling of the forest in the sliding strings. The brilliant juxtaposition of a high soprano with the otherworldliness of the counter tenor for Tytania and Oberon is a stroke of genius, and the different sound worlds of the rustics and the nobility is cleverly portrayed. Using boys for the fairies was a master stroke, along with the idea of a non-singing acrobatic actor for Puck, and, if there are occasional longeurs in the lovers’ quarrels, these are largely down to Shakespeare! The parody of Italian opera in the Rustics’ play is brilliantly effective, even down to Pyramus’s death being extended by an arioso, “Now am I dead”.

I only ever sang once in Britten’s ‘The Rape of Lucretia’ and so have no real experience of the work, and I always felt that the composer was let down by his librettist, Ronald Duncan, who came up with, in my view, the most awful florid nonsense, typified by the notorious line - “The oatmeal slippers of sleep creep through the city...” The Male and Female Chorus figures drag a heavy Christian dimension into the Classical story, and yet, there is much to admire in this early chamber opera, written for Kathleen Ferrier as Lucretia, and premiered at Glyndebourne in 1946. Similarly, Eric Crozier’s libretto for ‘Albert Herring’, taking a French story and dropping it into Suffolk sounds very dated now to my ears.

Since there is no role for bass in ‘The Turn of the Screw’, I had only seen it once, before I had to coach it at St Andrews University when the Byre Opera put it on with students. I found it a profoundly unnerving piece, turning a disturbing novella by Henry James into a terrifying story of supernatural corruption of innocence, with seriously creepy music.

‘Gloriana’, which Britten wrote as part of the Coronation celebrations for the new Queen Elizabeth in 1953, is a curious piece. Attended by the notoriously unmusical Royal Family at Covent Garden, and received in a lukewarm manner by public and press, it was rarely produced afterwards for many years. There has been a sort of revival, and in 2013, I understudied a couple of roles in a new Covent Garden production. Many people now see it as a neglected masterpiece, but I am afraid I found it rather tedious, and was very happy not to go on and perform in it.

I have no experience of performing the later operas and Church Canticles, and for some reason, never sang Noah in ‘Noye’s Fludde’, but must confess to finding much of Britten’s last decade of work slightly unsatisfying as a listener, although ‘Death in Venice’ has many felicities. Peter Pears’ portrayal of the old Gustav von Aschenbach was masterly, and I loved the role of the Voice of Apollo, sung originally by the peerless James Bowman, but the much sparser writing for both voice and orchestra fails to move me like the earlier scores.

In Part 3 of this look at Benjamin Britten, I will write about his magnificent War Requiem, a work of undisputed genius.